For me, connecting with nature in the time of COVID means I’ve been experimenting with nature apps to help make the most of my time in nature near me, which is primarily urban and suburban nature since I live near Washington, D.C. Not necessarily what anyone would consider pristine wilderness.

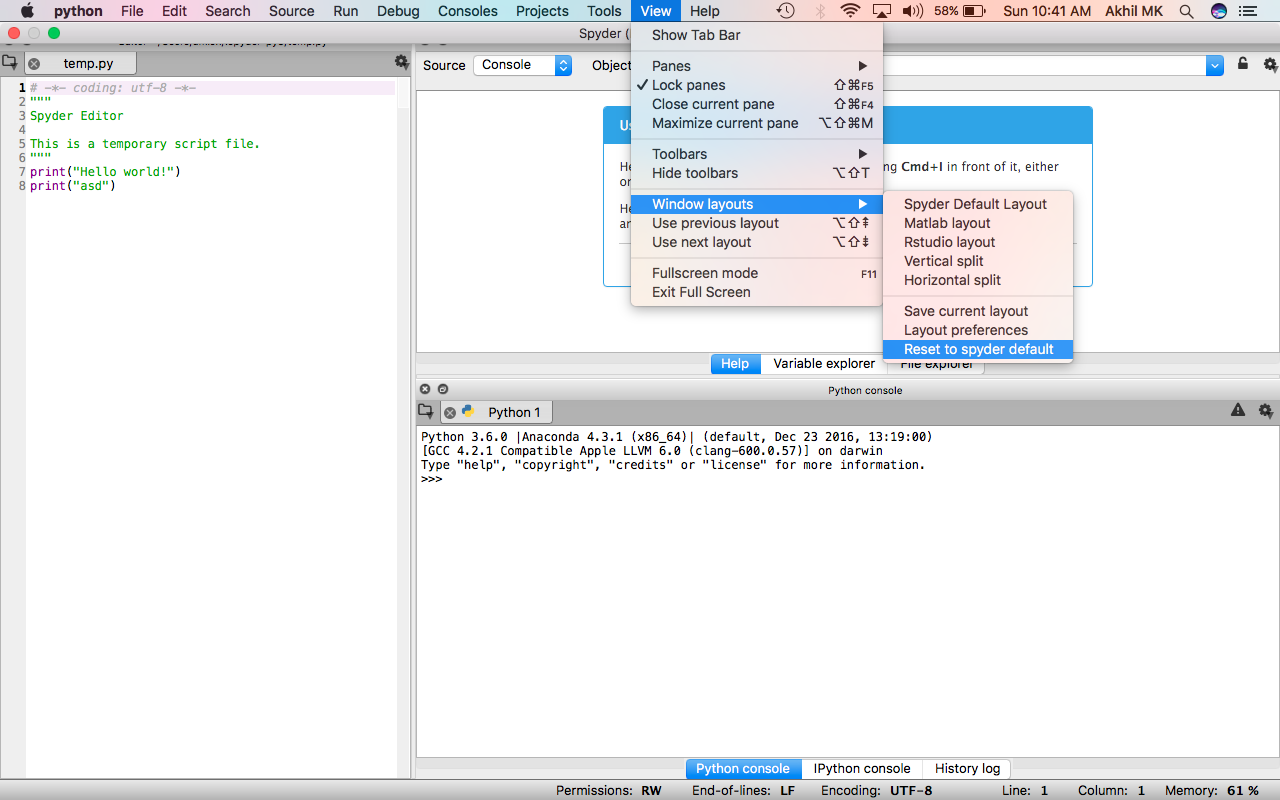

Spyder Keyboard Shortcuts for the Editor under Windows Conventional (more or less) Keyboard Shortcuts Home Go to start of line End Go to end of line Left Arrow Go to previous character Right Arrow Go to next character Up Arrow Go up to previous line Down Arrow Go down to next line Ctrl + Left Arrow Go to start of previous word. To access this app-specific Expose in OS X and display all of an applications open windows, move the cursor over an apps Dock icon and then do a three fingered swipe down. Because of its speed, maybe I'll jump into reviewing apps maybe. But for now I'll settle with reviewing hardware and the first piece of iPhone hardware I get to review, without borrowing someone else's device comes from the gang over at Spyder who have themselves a pretty neat piece of tech that's a match made in heaven for you iPhone power. This application is designed for and tested against versions up to 2.10.8, 3.5.10, 4.0.4, and 5.4.0 of Spyder software. Other versions of Spyder server software will likely work, however it is recommended that you upgrade to the latest versions of Spyder software available for your video processor for the best possible experience.

Related Articles

- Boucher’s Birding Blog: Apps for the Smart Birder — Which One Should You Use? By Timothy Boucher

- A Field Guide to Commonly Misidentified Mammals By Matthew L. Miller

- Ten More Field Guides and References for the Serious Naturalist By Matthew L. Miller

Over the last six months, I’ve played with subscription apps and downloadable field guides, and they definitely have their place. But these are the four apps I recommend most often to people who ask how they can learn more about the natural world around them.

Spyder In The Dock And As App For Windows

All of these apps are reliable, well maintained, science-based, accessible with most smartphones, don’t require paid subscriptions or other in-app purchases, and offer opportunities to contribute to the collection of field data. Two you can use without registering or revealing any personal information.

All four apps are also applicable beyond North America and suitable for engaging with nature wherever you find it — pristine natural areas not required. You can use these apps to id plants growing in cracks on city sidewalks, or insects and birds in shrubs and brush, as well as species found in city, state and national parks and protected areas and true wilderness areas.

If you have your own go-to favorite apps, please leave them in the comments. And stay safe out there.

Spyder In The Dock And As Appalachian

I love this app. Since the new version launched earlier this year, it is hands down my most recommended nature app for friends asking for ways to up their knowledge and enjoyment of urban, suburban and wilderness nature exploration.

Want to know what that plant is growing in a sidewalk crack in your neighborhood? Snap a quick image with the app and odds are Seek can identify it for you. I’ve used the app to ID a spider on a friend’s dock (dark fishing spider), a fat green beetle that found its way into my house (eastern Hercules beetle), and the plant that my dog always seems to want to roll in (cat mint, go figure). Be warned though, Seek can be very addicting. That goes double if you’re exploring with children. You’re likely to learn all kinds of new things, but your mileage — if you’re going for distance — will definitely suffer.

A collaboration between iNaturalist, the California Academy of Sciences and National Geographic, having Seek in your pocket can be like traveling with experts in nature identification, from plants to insects, mammals, birds and even fungi!

As noted on the Seek blog, “The species included in Seek are based entirely on photos and identifications made by the global iNaturalist community, so the Seek camera will work best in places where there is already an active community of iNaturalist users, and for species that are easily identified from photos. Unlike iNaturalist, findings made with Seek will not be shared publicly, making it safe for children to use.

Seek is powered by iNaturalist, which is the best app I know for discovering and identifying plants and animals from your backyard to the backcountry. And not just in the countries of North America, but all over the world. With iNaturalist, you are also contributing to recording and documenting biodiversity because the data is accessible to scientists.

The iNaturalist site also offers a wealth of opportunities for connecting with others and contributing to science, from hosting and participating in bioblitzes, to tracking and maintaining your personal nature observation life list, to crowd-sourcing identifications for those hard to ID sightings.

iNaturalist is “a place where you can record what you see in nature, meet other nature lovers, and learn about the natural world. [It’s] an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature. You can use it to record your own observations, get help with identifications, collaborate with others to collect this kind of information for a common purpose, or access the observational data collected by iNaturalist users.”

The app also works without wifi or cell coverage. It can take a little bit of patience to get up to speed on how to make the most of it, but iNaturalist richly rewards the time invested in learning how to use it. (And if you love Seek, becoming a registered iNaturalist user means you’re contributing to improving the capabilities of the companion app.)

I’ve been using Merlin, from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, since I started my journey to becoming a (moderately) competent birder in 2015. My love for the app is widely known and it has only gotten better and more lovable over the years. I recommend this to anyone who will listen, including complete strangers on hiking trails in Olympic National Park. Today, the app, which is free, includes “bird packs” for every continent except Antarctica. As of August 2020, Merlin has content for 7,500+ species. Check the Bird Packs screen in Merlin to see the full listing of packs.

In one of the many improvements since 2015, you can also upload images and Merlin will suggest matching birds.

Also from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, this is a kind of companion app to Merlin — similar to how Seek relates to iNaturalist. To use Merlin, you don’t need to create an account or otherwise register. For eBird, you will need to create an account. eBird enables birders track their sightings in birding lists. (I confess, I’m not a listing birder in the traditional sense.)

But for people who love listing (and contributing to science), as well as a social element, eBird is a great app for all of the above. Even though I don’t keep a traditional list, I do have an eBird account so I can get the notification emails about bird sightings (especially unusual or rare species) near me. eBird also helps birders connect to each other in the “world’s largest birding community” and tracks their lists, and archives photos and recordings. All for free. Data contributed by eBird users are “a powerful resource for a wide range of scientific questions. eBird Status and Trends highlights Cornell Lab analyses of continental bird abundances, range boundaries, habitats, and trends.”